I’m not really certain what it was written for, but I remember the big letters on a slip of paper: IOU.

Maybe I’d borrowed a few dollars from a friend. Maybe a teacher had loaned me a pencil and wanted it back. My memory is pretty good, but it’s not perfect. Clearly my spelling and grammar still needed some work too. But the idea itself was clear enough. An IOU. An I owe you.

That simple concept is the building block on which our entire monetary system is built: debt.

That idea came roaring back recently during a conversation with my son about Scott Galloway’s notion of men creating “surplus value.” I haven’t read the book, but I’ve listened to enough interviews to understand the point. Give more than you take. Produce more than you consume. Contribute something of value that didn’t exist before you showed up.

In monetary terms, creating surplus value means that someone owes you something. That “something” is what money was meant to represent in the first place.

Pulling in the opposite direction is J. Wellington Wimpy from Popeye the Sailor Man. His immortal line was that he would “gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today.” Wimpy isn’t interested in surplus value. He’s interested in the now. He wants the benefit immediately and pushes the obligation off into the future. That’s credit. Getting before you’ve given. Consumption untethered from contribution.

Between those two simple ideas—IOU and Wimpy—there’s a lot to be learned about what money actually is, and how far we’ve drifted from its original purpose.

Money was meant to be a systemic IOU. A marker that you had already provided goods or services to someone else. You could then pass that IOU along to another person in exchange for what you needed. If you consistently created surplus value in the world, you accumulated surplus money. If you didn’t have enough in the moment, you could borrow—paying a premium in interest for the privilege of consuming before contributing.

On a small scale, the logic is intuitive and fair. You mow a lawn. You teach a class. You fix a car. Value is created. An IOU is issued. Trust is maintained.

As the scale expands, things get murkier. Someone like Howard Schultz, for example, has created surplus value that touches millions of lives every day. Jobs, products, routines, communities. Quantifying that impact is difficult, but few would argue that it exists. The system is supposed to reward that kind of value creation proportionally.

Where the tension really shows up is at the national level.

Our government has repeatedly devalued our collective IOUs while playing Wimpy on the international stage. Promising Tuesday. Borrowing endlessly. Printing claims on value that hasn’t yet been created—and may never be. When that happens, the IOUs held by ordinary people quietly lose meaning. The surplus value they worked to create gets diluted, siphoned off, and often frittered away.

It becomes harder and harder for the average person to get ahead, not because they aren’t producing value, but because the measuring stick keeps shrinking. You can do everything “right” and still feel like you’re running uphill on loose gravel.

Money, at its core, is a story we agree to believe. An IOU that says, I have contributed, and I will be able to draw from that contribution later. When that story breaks down—when IOUs are issued faster than value is created—the trust erodes. And without trust, the paper is just paper.

Maybe that’s why that old slip with “IOU” written on it sticks with me. It wasn’t just about owing someone a pencil. It was a lesson, early and imperfect, about responsibility, reciprocity, and keeping your word.

Tuesday eventually comes. The question is whether the hamburger ever gets paid for.

Be valuable today!

Pete

The 90s had many memorable events and people. Kurt Cobain, the OJ Simpson trial, Monica Lewinsky and Bill Clinton were all extremely noteworthy. Both for their own unique reasons and the media circus that followed them. It was not just that something happened but that it was perpetuated daily for probably longer than needed. One of the most ridiculous stories of the decade was the ice skating scandal involving rivals Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding. For those too young to remember, the major event was an attack on Kerrigan’s knee orchestrated at least partially by Harding’s ex-husband. There was a movie released last year called “I, Tonya” that chronicles the entire episode.

The 90s had many memorable events and people. Kurt Cobain, the OJ Simpson trial, Monica Lewinsky and Bill Clinton were all extremely noteworthy. Both for their own unique reasons and the media circus that followed them. It was not just that something happened but that it was perpetuated daily for probably longer than needed. One of the most ridiculous stories of the decade was the ice skating scandal involving rivals Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding. For those too young to remember, the major event was an attack on Kerrigan’s knee orchestrated at least partially by Harding’s ex-husband. There was a movie released last year called “I, Tonya” that chronicles the entire episode. So I implore you. Yep! I’m talking directly to you because as I said last week,

So I implore you. Yep! I’m talking directly to you because as I said last week,

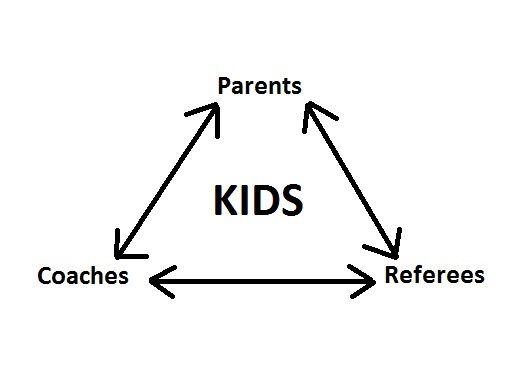

With the World Cup only a week away, the passion of nations is about to be put on display for the world to see. The line between ecstasy and exasperation will be measured in moments and inches rather than hours and yards. Preparations for this spectacle have been going on for years because for most of us, it is just that big of a deal. Soccer truly is its own religion. The problem, however, is the same as it is with most religions. When people care that much about something, they tend to leave their ability to reason at the door. Passion trumps perspective and people lose sight of what is TRULY important. This is extremely evident in soccer’s hate triangle*.

With the World Cup only a week away, the passion of nations is about to be put on display for the world to see. The line between ecstasy and exasperation will be measured in moments and inches rather than hours and yards. Preparations for this spectacle have been going on for years because for most of us, it is just that big of a deal. Soccer truly is its own religion. The problem, however, is the same as it is with most religions. When people care that much about something, they tend to leave their ability to reason at the door. Passion trumps perspective and people lose sight of what is TRULY important. This is extremely evident in soccer’s hate triangle*. This past weekend at my son’s game, it became evident that there are a lot of negative feelings swirling around the soccer fields these days. There is obviously plenty of excitement and passion to go around but the negative feelings are also ubiquitous. Most of the time these feelings are directed at a particular group of people involved. Every game has the potential to become a powder keg as tempers (both expressed and unexpressed) flare up. Three groups represent the biggest sources of animosity and project it outward toward one or both of the others. Coaches, Parents and Referees are the adults surrounding a game. While stuck in the middle are the young people that the game is supposed to be for. Obviously not every parent, coach or referee has these negative feelings toward the other groups but it is so ever-present that most kids are affected.

This past weekend at my son’s game, it became evident that there are a lot of negative feelings swirling around the soccer fields these days. There is obviously plenty of excitement and passion to go around but the negative feelings are also ubiquitous. Most of the time these feelings are directed at a particular group of people involved. Every game has the potential to become a powder keg as tempers (both expressed and unexpressed) flare up. Three groups represent the biggest sources of animosity and project it outward toward one or both of the others. Coaches, Parents and Referees are the adults surrounding a game. While stuck in the middle are the young people that the game is supposed to be for. Obviously not every parent, coach or referee has these negative feelings toward the other groups but it is so ever-present that most kids are affected. The role of a captain can be very important on a soccer team. I say “can be” because on some teams, the captain does nothing more than the coin toss. My perspective is that the captain has a great deal of responsibility and should have certain characteristics that help her to lead.

The role of a captain can be very important on a soccer team. I say “can be” because on some teams, the captain does nothing more than the coin toss. My perspective is that the captain has a great deal of responsibility and should have certain characteristics that help her to lead. Most of the time soccer is a noun but today I’m going to use it as a verb. Of course when you are creating a new word, it’s important to define it. Here is my explanation of the term.

Most of the time soccer is a noun but today I’m going to use it as a verb. Of course when you are creating a new word, it’s important to define it. Here is my explanation of the term. The 20th Century of the United States was largely dominated by an industrial economy. The US rode the wave of the industrial revolution into prominence on the world stage. Factories flourished thanks to interchangeable parts and largely interchangeable people. Most workers in the 20th Century were able to earn a substantial living by doing simple repetitive tasks under the orders of their bosses.

The 20th Century of the United States was largely dominated by an industrial economy. The US rode the wave of the industrial revolution into prominence on the world stage. Factories flourished thanks to interchangeable parts and largely interchangeable people. Most workers in the 20th Century were able to earn a substantial living by doing simple repetitive tasks under the orders of their bosses.

I have often wondered what history lessons are like in Germany about the period between 1900-1950. From an outside perspective it is easy to characterize Germany as the villain of that epoch. Is it viewed as a period of shame? Or glossed over as unfortunate past events? Often people and nations have a hard time seeing themselves as others would see them. When looking at others, it is easier to make judgment that we believe is right. We can see their faults, shortcomings, idiosyncrasies and failures. Or we laud their beauty, strength, courage or “perfection”. Self-reflection is usually skewed in either a positive or negative direction. People, just like nations, have a history that they must reconcile in order to move forward. Recently upon thinking of Germany’s past and looking in the mirror, I reflected on what nation I represent.

I have often wondered what history lessons are like in Germany about the period between 1900-1950. From an outside perspective it is easy to characterize Germany as the villain of that epoch. Is it viewed as a period of shame? Or glossed over as unfortunate past events? Often people and nations have a hard time seeing themselves as others would see them. When looking at others, it is easier to make judgment that we believe is right. We can see their faults, shortcomings, idiosyncrasies and failures. Or we laud their beauty, strength, courage or “perfection”. Self-reflection is usually skewed in either a positive or negative direction. People, just like nations, have a history that they must reconcile in order to move forward. Recently upon thinking of Germany’s past and looking in the mirror, I reflected on what nation I represent. The shoehorn*, crowbar and bulldozer; all use a combination of an inclined plan and a lever. While they all have the same base components, almost no one would ever use one as a replacement for the other. Using a bulldozer to get your shoes on could get messy really quickly! It’s overkill and everyone can see that.

The shoehorn*, crowbar and bulldozer; all use a combination of an inclined plan and a lever. While they all have the same base components, almost no one would ever use one as a replacement for the other. Using a bulldozer to get your shoes on could get messy really quickly! It’s overkill and everyone can see that.